A House of Dynamite, Kathryn Bigelow‘s 2025 movie, is a fascinating film for its dramaturgy and showing an eye for details around all things happening in the moment, but also from a philosophical perspective. What makes it stand out is how it shows something new about distributed cognition, political decision-making and sovereignty.

The film is structured in three segments, each revisiting the same 19-minute window from different perspectives. These 19 minutes follow the detection of a ballistic missile heading toward the United States. At first, it’s dismissed as a false alarm, expected to fall into the Pacific. But as the threat becomes real, the system aligns towards a coordinated response.

- The first segment focuses on the Situation Room at the white house and a military base in Alaska. We see captain Olivia Walker coordinating communications in the situation room, the lieutenants launching the interception devices, and their shock when the system fails. The tension is palpable as the machinery of defense begins to falter. And it’s all a tension behind screens. This is a war started and tackled from behind a screen: technological horror at its best.

- The second segment shifts to an NSA adjunct, Deputy National Security Advisor Jake Baerington, who must step in when his superior is unavailable. This is his big break, career-wise, but career is the least of his concerns in this moment. Jake tries to de-escalate the situation, urging against a blind counterattack. He senses that once retaliation begins, it cannot be undone. Despite his emotional intelligence and intuition, he lacks the authority – and perhaps the rhetorical skills – to stop the momentum. He just doesn’t find the right words in this situation but perhaps, as the movie suggests, there are no right words to say here to stop the apparatus of the nuclear launch.

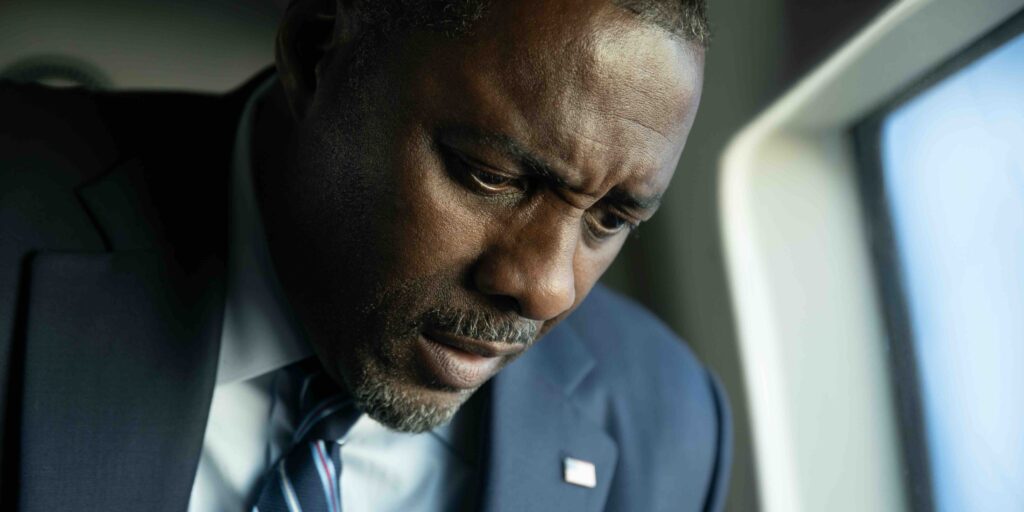

- The third segment centers on the President. The film shows how he comes to the decision to launch a nuclear strike. Interestingly, the ending- what many viewers expected to be a climactic moment- is actually the film’s opening shot: a mushroom cloud. The decision has already been made; the rest of the film unpacks how it came to be. Many commenters on IMDB were disappointed because they were denied this clear ending, and I hear them, but there was only one ending possible. It’s highly improbably that POTUS decided on anything else but the launch, and the actual target chosen for this is irrelevant – from his menu of options of targets which are described as “rare, medium rare, and well-done”. Whatever the target of his choice, it’s a coin toss, a random decision. There is no justice in this decision, just a show of power.

The movie and its structure shows something horrifying: the decision doesn’t belong to any one person. It is the product of a tightly interlocked system of institutions, protocols, and roles. The President appears to have agency, even briefly considering not launching the strike. But the system around him – advisors, military officers, aides, secretaries, protocols – makes his inaction nearly impossible. As POTUS puts it, the system exists so that “people know not to mess with America.” This is the system: sending a message of fear to the rest of the world. It’s not about justice or punishment, just a message: we will retaliate if you mess with us.

Philosophically, I found the movie intersting for two reasons, what it says about:

- Distributed cognition: Intelligence and decision-making are not confined to individuals but emerge from networks of people and systems working together. This we know already, intelligence can work distributed, and wisdom of the crowds is great for estimating the weight of a pig at a fair. But what the movie shows is that distributed cognition can work very well towards a wrong decision, a decision which makes no sense. All these smart people scattered across various locations, connected by one videoconference call, can make a wrong decision.

- Systemic sovereignty: Political decisions, especially those of massive consequence, are not owned by individuals. They are embedded in institutional machinery that both enables and constrains action. The decision of the sovereign, in this case POTUS, was taken by the system even before he was elected. He happens to be the one who blesses this, give the voice command, but it’s irrelevant who is the one assuming it.

Even moments of personal resistance – like the NSA adjunct’s pleas or the Secretary of Defense’s suicide – are absorbed by the system. Individual actors side-step the system but not to challenge it, rather to find small pockets of personal interests: they try to call their families, to act as individuals, but they remain cogs in a machine designed to function regardless of human emotion or intuition. They continue to do their duty after calling their relatives, they continue to power the decision-making machine. This is seen as duty. The system selects for those people who will do their duty unquestioningly, without flinching.

One of the most striking aspects of House of Dynamite is how it frames the “enemy.” Countries like Russia, North Korea, and China are referred to as enemies, even though there is no declared war. This rhetorical move-labeling them as enemies-makes it easier to justify launching a nuclear strike if they are suspected of being behind the missile. The word “enemy” becomes a cognitive shortcut that simplifies a morally complex decision. This word is used repeatedly by lieutenant cmdr Reeves, the one who follows the president carrying always the briefcase with the list of nuclear targets, the “menu” of options.

The film showcases how distributed cognition works in this decision, but not in the benign sense of the “wisdom of the crowd.” It’s about a system made of humans computing a decision, yet one that is already heavily constrained. The president always carries a card with nuclear codes. Generals are trained to wait for the order. And when the moment comes, they want to hear that order – not out of bloodlust, but they were trained to wait and expect it. The president’s word is treated almost like a religious blessing that allows them to act.

Yet not all cogs are equal in this machinery of distributed cognition. One general in the nuclear command room remains eerily calm, sipping coffee and chatting about sports, as if retaliation is the only logical next step. The only real opposition comes from the NSA adjunct, who tries to stop the spiral. But even he is part of the system – his role is to provide information, not to halt the process.

This raises a question: distributed cognition is often praised for enhancing collective intelligence. And indeed, the people involved are smart, capable, and emotionally aware. But in this case, the system channels their intelligence toward a single, catastrophic outcome. Distributed cognition, when embedded in a rigid system, accelerates rather than questions the path to destruction. There is no way to take a right decision from inside the system. The moral values needed to be designed and embedded in the system before it was set into motion. The moral decision was long ago, before any of these things happened, in deciding how the actors were supposed to interlock and which duties were distributed. The more we diffuse responsibility along this chain of decision-facilitators, the more the system needs to be rethinked to make possible alternative outcomes. To reiterate my point, the decision not to fire those nukes as retaliation was not a viable option in the president’s menu of choices. The system needed to be different to allow for even entertaining this option seriously.

Funnily enough, no one asks ChatGPT or any external AI system for help. AI can only make mistakes – someone mentiones that perhaps the first missile was wrongly fired by a malfunctioning AI system in the Pacific. The NSA adjunct relies on his own memory and statistics. This is distributed cognition, but not extended cognition, all intelligence available is confined within a closed loop of human actors trained to think in a particular way. Nobody extends or delegates the cognition needed to make this decision happen. All people have their brains to rely on, and this is it.

The other philosophical theme that was striking was sovereignty. In political theory after Agamben, the sovereign is the one who decides who lives and who dies – who is inside the law and who is placed outside it. In this case, the President (POTUS) is the sovereign, but his decision is not truly his own. The system has placed him there precisely to take responsibility for a decision that no one else wants to own, but it’s also not his. His personality, emotions, or moral compass are irrelevant. This shows a paradox of democracy: we elect someone not to think freely, but to function as a cog in a machine that must keep running. The actual person behind the POTUS role is irrelevant. The actual choice – of who gets elected for this role – is irrelevant, provided they are not a raging lunatic who side-steps the system completely.

To prevent such a decision, an altogether different kind of system would be need to put in place: one that doesn’t push so hard toward the nuclear option. It would require different education of the main actors, different risk assessments, and a broader view of global responsibility, and some accountability for the very architects of the decision making system itself. But the current apparatus ensures that no one thinks beyond their national corner: the system is meant to protect Americans, in spite of the rest of the world. The decision is about who gets to shoot first their missiles. And the issue here is that all other countries with nuke capabilities will think exactly the same, it’s not the U.S. as a special case here, albeit they do have more power on their hands.

A House of Dynamite showcases this sovereign logic in which one country decides who is allowed to live in the rest of the globe, albeit they decide it knowing it’s suicide and will lead to their own destruction. And the justification is chilling: if we don’t make this decision, someone else will-and better us than them.

Later addition: Reading an expert’s commentary on the movie, it seems that the movie oversell the failure of the system and is not true to what would happen in real life: multiple attempts that compound to higher succes rate for intercepting. It also states that the president would not be forced to decide right away where to retaliate, and that the leadership would hide while gathering information. The movie has to cut some realistic options to make it more dramatic and to show us the moment of decision as madness – following Derrida’s misreading of Kierkegaard. This is reassuring to know, but the fact of distributed intelligence remains and that the system itself is, in how it is built, endorsing certain values that are not up for debate. The system’s architecture is the sovereign, while the sovereign remains a blessing, a speech act that launches, a formality, a magical act. That, I think, remains.

Leave a Reply